“Fish,” casein on board, 1952

In 1951, Joe realized that Pasadena was well past its heyday as a winter resort for the wealthy and closed the fur shop. They purchased a chicken ranch in Arcadia, CA. Dorothy often said that Joe was never happier than when he ran this egg ranch with 4,000 laying hens. Her father and step-mother, Harry and Minnie Browdy, moved into a small rear house and Dorothy kept one of the unused barns as a studio. This first studio had low ceilings and was dark and beastly hot in the summer. It served her (and later her son, Robert) as a studio for these transitional years during which her experiments rapidly became more and more progressive. Her father set up a wood shop in the next section of the barn and made frames out of old wood for many of his daughter’s paintings. Joe continued this tradition of framing Dorothy’s work after Harry’s death in 1962.

Dorothy began to visit the old Pasadena Art Museum that housed the extensive Galka Scheyer Collection of German modernist works of the Blue Four: Lionel Feininger, Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Alexei Jawlensky. The Pasadena Museum also had a very progressive exhibition program under its director Walter Hopps. Here, Dorothy viewed retrospectives of Chagall, Nolde (whose floral watercolors inspired her), Pop Art, Cornell, Schwitters and Duchamps. In this heady mix, Dorothy was drawn most strongly to the cubist inspired geometric abstractions of Feininger and soon began to experiment more fully with modernism in her own work.

She called her new paintings based on Feininger her “Prismatic Series.” She painted on board or paper with ink and casein, a water-soluble paint derived from milk casein. Casein paint is fast-drying, easy to clean up and opaque with more permanence and “body” than transparent watercolor. She began each work with a representational drawing, and then introduced black, white and gray stippled bands of paint to extend and abstract the forms within her compositions. The chroma was cool and silvery, often with primary accents. Many of these paintings were landscapes and trees, particularly a Chinese Elm tree and an Acacia tree on the property. Naturally, chickens and ducks from the chicken ranch became subject matter as well as boats, children, fish — she “prismaticized” everything she could think of. While some of her later New York pieces embraced deco, here she was creating works that pleased her with their stark, unapologetic modernity.

“Buoyant Force,” casein on board, mid 1950s

Around 1953, when the chickens were sold, Dorothy moved her studio to the larger, lighter brooder barn. Light and space were plentiful, and the work began to change as well. Leaving behind the “Prismatics,” she tried a number of different approaches in rapid succession. Black and gray dominated. Very wet ink and watercolor landscapes on paper or board. Expressionistic oil landscapes on masonite, with rough brush strokes and drips. She worked on a series of very thickly painted oil paintings on board, inspired by the highly textured surfaces of late Monet paintings where the surface was built up with many layers of paint creating a thick encrusted surface over which her gliding brush left the surface composition.

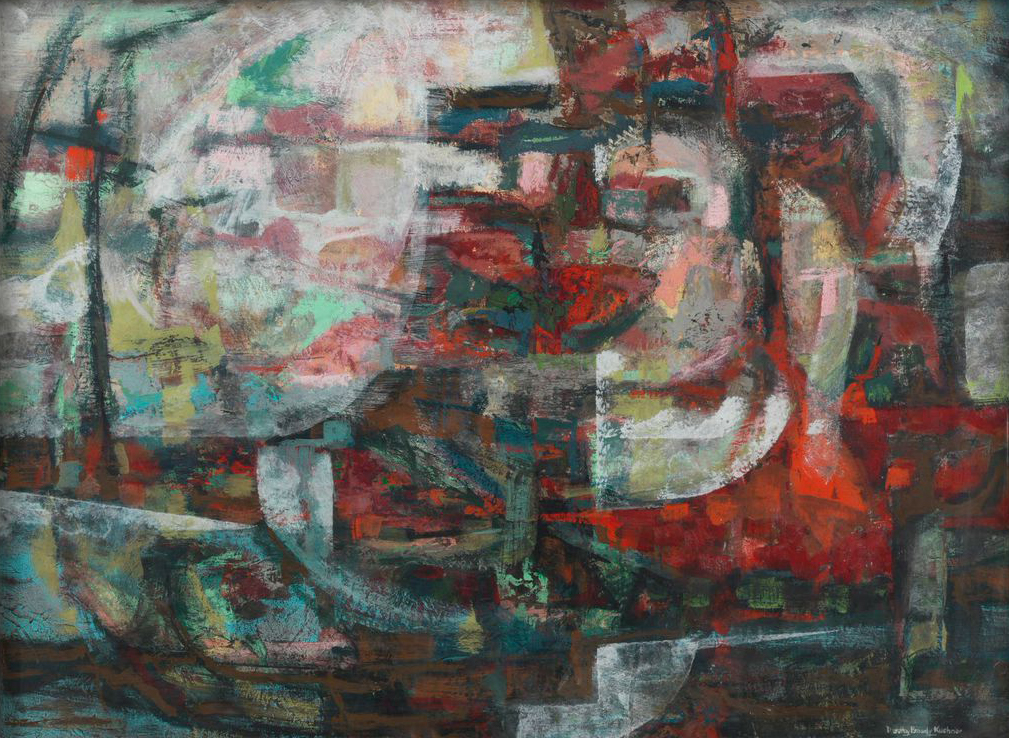

Sometime in the mid 1950s Dorothy encountered the monumental paintings of Richards Ruben (1925-98). His works were exhibited at the Pasadena Museum of Art which may be where Dorothy first saw them. They were large and authoritative, painted with gutsy bravado, strongly influenced by Clyfford Still and the other abstract expressionists. Hans Hofmann’s theories of paint handling, composition and color were dominant. “I wanted something different from the stuff I was doing, and so I took the class and he [ Ruben] was teaching … we met at the park, and that’s where I met all the Arcadia people that I knew that were in art [i.e. The Group]. I think he was quite influential in my life, changed my whole style from realistic [to abstraction].” Dorothy attended and listened carefully and her work changed dramatically. Her landscapes became more abstract, focusing on close up views of rock formations that she derived from newspaper and magazine photos. Her palette cooled to browns, greens, black and gray. Her brushwork and composition were decisive and uncompromising.

“Rocas,” casein on board, mid 1950s

She was also inspired by the virtuoso brushwork of Franz Kline—particularly his late, color work—and by the impasto forms of Nicolas de Stael (1914-55). It is not clear how aware she was of the Bay Area abstractionists at this time. Later she came to admire Richard Diebenkorn’s paintings. She was acquainted with Lorser Feitelson, Helen Lundeberg, and other prominent California progressive painters through the Los Angeles Art Association. But their form of hard edge abstraction held little interest for her. She also knew and respected June Wayne and Betye Saar. To keep up with the newest trends, she followed exhibitions at the galleries at that time centered around La Cienega Boulevard (she saw and was understandably shocked by Andy Warhol’s notorious show of Soup Cans in 1962), as well as the shows at LACMA and the Pasadena Museum.

From 1955 to 1972, a group of like-minded women abstract painters met monthly to analyze and critique each other’s work. They called themselves The Group.

Erle Loran’s book, Cezanne’s Compositions, became Dorothy’s bible. Her copy of Loran was often out in the studio and she frequently consulted it for inspiration. She was fascinated by Cezanne’s use of warm and cool tones of the same colors. One can see Cezanne’s chromatic influence on her subsequent paintings with her flurries of warm and cool greens, blues, browns, even reds in each painting. She became adept at combining color out of the tube with an entire range of mixed color compliments. Loran emphasized Cezanne’s use of directionality of form to lead the eye around the composition and Dorothy followed this lead as well.

After her rocky landscapes she returned again to one of her great strengths—color. She became drawn to the work of Pierre Bonnard and would often take a reproduction of a Bonnard painting, isolate a small corner of it as the beginning of a new painting both for his rich color harmonies and the cropped composition. At this time she expanded her landscape explorations to include still life and floral compositions. Flowers remained a very important part of her work for the duration of her painting life. The flowers offered new color harmonies as well as softening of her forms.

“Purple Flowers,” diptych, oil on masonite, 1962

The abstract expressionist approach to direct painting with gestural brushstroke lent itself well to her landscapes and flowers. Purple Flowers diptych offered her the color purple to explore, but contrary to the curvaceous forms of the flowers and leaves, she maintained a vigorous gestural angularity. The two panels were hung approximately six inches apart, and it was a formal challenge for her to have the dynamism of her forms link these two separate panels. Oncoming Storm featured a welter of shifting forms in sharp clear greens with scumbled olive drab in the foreground with a dark ominous sky above. Over time the softness of the flowers themselves started to influence her brushwork. Sometimes she painted directly from nature and then began to abstract and simplify the forms back in the studio. Like Georgia O’Keefe, another artist whom she admired, she often zoomed in for extreme abstract close-ups of the botanical forms. Gesture and color remained her primary interests. The color red, with its many variations, became a passion.

She exhibited her work in solo shows in several galleries during these years. In 1961, she mounted a large group of recent oil paintings at Ramon Lopez Gallery in out-of-the-way Sierra Madre. Lopez understood and encouraged her work. The exhibit was strong, consistent and individual. It was one of the only times she saw her work in a clean, open, well-lit space, far from the studio. The individual works looked forceful and energetic, full of rich color harmonies, but did not attract sales which was discouraging. (Purple Flowers and Oncoming Storm were in this show). She was regularly invited to exhibit at local libraries and liked seeing her work in new contexts, out of the confines of the studio. She also entered numerous juried exhibitions, and several paintings were selected for LACMA annual competitions. She exhibited regularly at Los Angeles Art Association, California Watercolor Society, Pasadena Society of Artists and Laguna Beach Art Association. Several times, she served as a juror or officer.

She exhibited her work in solo shows in several galleries during these years. In 1961, she mounted a large group of recent oil paintings at Ramon Lopez Gallery in out-of-the-way Sierra Madre. Lopez understood and encouraged her work. The exhibit was strong, consistent and individual. It was one of the only times she saw her work in a clean, open, well-lit space, far from the studio. The individual works looked forceful and energetic, full of rich color harmonies, but did not attract sales which was discouraging. (Purple Flowers and Oncoming Storm were in this show). She was regularly invited to exhibit at local libraries and liked seeing her work in new contexts, out of the confines of the studio. She also entered numerous juried exhibitions, and several paintings were selected for LACMA annual competitions. She exhibited regularly at Los Angeles Art Association, California Watercolor Society, Pasadena Society of Artists and Laguna Beach Art Association. Several times, she served as a juror or officer.

By the mid 1960s, acrylic paint was widely available and affordable to artists. This was the answer to many of Dorothy’s problems with oil paint. Acrylic paint had a color intensity matched only by oil. It dried quickly and was easy to clean up. She had become frustrated with the matte, slightly chalky quality of casein which need to be framed with glass to protect the surface. With acrylics, she could paint on paper, board or canvas and the surface was durable enough that glass was not necessary. Her chromatic explorations took off into realms of red landscape, blue skies and water, yellow autumnal trees, all colors of flowers. Her landscapes often featured very high horizon lines so that the diagonally receding planes of the foreground became the primary focus of the painting. In other works, she introduced dramatically low horizons that allowed her to experiment with large expanses of clouds and sky. Flower studies became nearly abstract expressions of striped color fields. This was a richly productive period for Dorothy.

Around this time she also began teaching again, since Joe was no longer able to work due to heart disease. At first, she was a substitute teacher in the Arcadia junior and senior high schools. Soon she went on to teach college level courses in drawing and painting at Pasadena City College, Rio Hondo College and Orange Coast College. She was very devoted to her students and loved being in the classroom again.