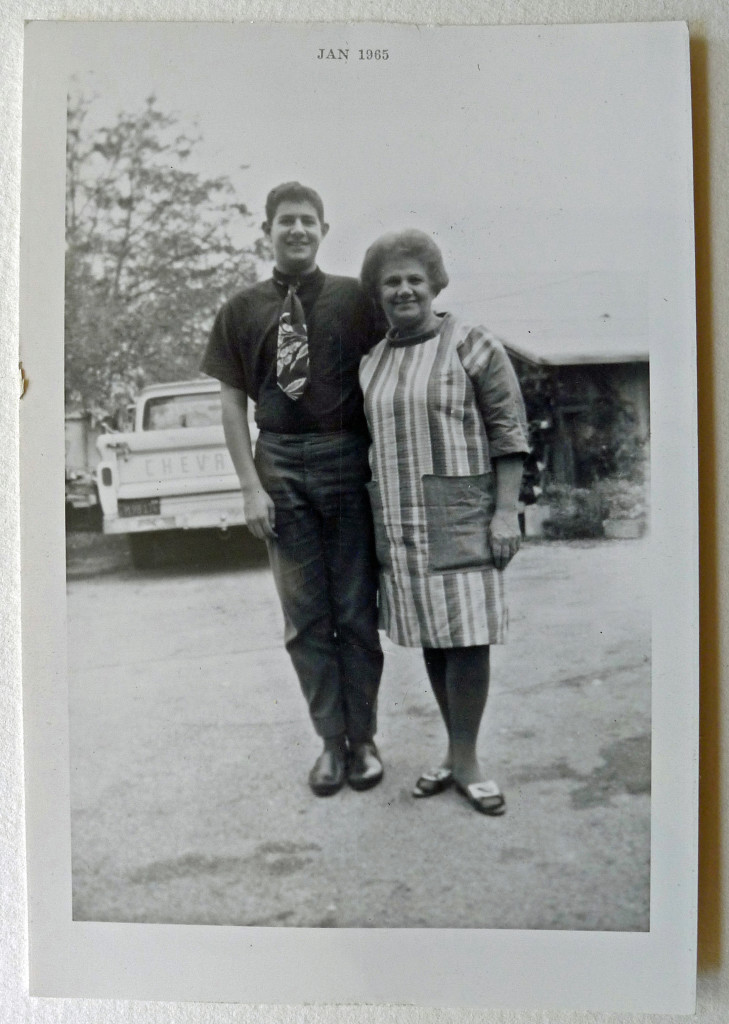

Robert and Dorothy Browdy Kushner, 1965

“Dorothy Browdy Kushner…transmitted her graphic flair

to her well-known son, the artist Robert Kushner.”

Holland Cotter, The New York Times, 11.3.2006 ________________

During my childhood, there was nothing more interesting than my mother’s studio: big, odd, eccentric, full of energy and always full of ideas. A decaying taxidermied deer hovered over the door. The word “Studio” in her bold calligraphy – white on the dark green wall. Outdoor tables, metal racks and hanging pots of succulents populated the space. The old dress mannequin left over from the fur business with arms that could be rearranged into the most alarming tableaux. The big work table, cleared off periodically for large parties or printmaking sessions. And, of course, her most recent abstractions on easels, changing, morphing on a daily basis.

When The Group came over, and when I did not have to be in school, I was in heaven. I watched and listened and marveled. How they could examine and analyze a painting or drawing, pick it apart and kindly offer suggestions on how to make it stronger! In the words of Simone Weil, there was an awareness, respect and “Love of the beauty of the world . . .the love of all the truly precious things that bad fortune can destroy. The truly precious things are those forming ladders reaching toward the beauty of the world, openings onto it.”

Compare this to the male gatherings of that era. After dinner, the men would congregate around the kitchen table, Grandpa Soll smoking disgusting smelly cigars, my dad his Chesterfields, all playing pinochle or poker, while talking about stock prices. There was no contest.

In my family, specific gender defined roles were somewhat blurry to start with: men and women all cooked—different things. Dorothy did most of the daily cooking but Grandpa Browdy made his own wine and specialized in a hearty marrow bone soup. My dad cooked odd seasonal dishes (which my mother did not want to make): potatoes with egg and raw onion, summer salad of cottage cheese with sour cream and lots of raw vegetables. And, everyone knew how to sew. Dorothy made all her own clothes; Joe and his brothers were adept at the sewing machine from early years in the fur trade. Grandma Browdy made or reconfigured a new hat for every Saturday’s morning services. But Dorothy and her friends made art.

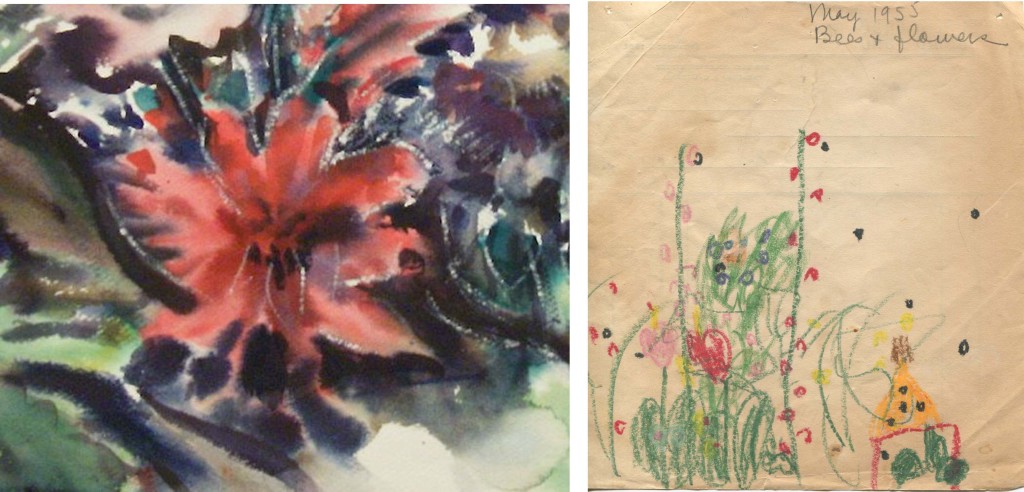

”One of my earliest memories was painting side by side with my mother. I always was given good art materials to work with, either by Dorothy or her friends.” — Robert Kushner, 2011. Left: Dorothy Browdy Kushner’s “Cannas and Acanthus,” (detail), 1948. Right: Robert Kushner’s “Bees and Flowers,” 1955 (age 6).

My mother could be a tough teacher. At about age nine, I became interested in mosaic. She gave me many pieces of colored matte board, cut into small squares that I could paste down and then lacquer over to create a faux mosaic. Before cutting the pieces of matte board, I made drawings for designs: a swamp and an underwater scene. She viewed this as a teaching opportunity. “You need to pay more attention to the edges,” she said, as she re-drew the plant forms and butterfly wings directly over my little sketch, extending and exaggerating them to touch the sides of the composition. She showed me how to activate the “negative spaces.” The resulting maquette was more her work than mine—and I was furious. But I could not disagree with her corrections as she had dramatically emboldened the composition by the time she was done. That lesson, and others like it, taught me composition, space and even color.

When I took a life-drawing course in college with no anatomical instruction. (My professor: “Look at the figure and your eye will tell you exactly what you need to know.” Very 1960s.) My mother thought this was ridiculous and got out her old anatomy books. She showed me how the major bones and muscles related to each other. Then she showed me how to draw faces, hands and feet – a horizontal line here, a trapezoid there. She also really knew color. Who else knew that cadmium yellow with the slightest touch of black yielded a lovely olive green? We often played a color mixing game: one of us would choose some object that was an odd shade, and then together we would try to figure out how to mix that color with paint.

There was always a double standard between my “real” career and art making. The message seemed to be: make art and express yourself, but don’t get too involved, as you still need to become something bankable. Since I liked plants, terraria and aquaria, and was good at math and science, this respectability seemed to center on research science. That having been decided, I still always had my own art materials, good ones, and a set of drawers in the dining room where I could store them. When Dorothy would drive her friends’ artwork across town for a juried show, she would not take gas money from them. Occasionally, as a thank you to her, they would give me good quality art supplies: a wooden box with a set of luminous Dutch pastels, a large set of oil pastels, a block of watercolor paper. These were my treasures, and I spent considerable time thinking about how to use them well. I was always making something at the dining room table–watercolors, paper mosaics, crayon resist, scratch boards, collage. While still in high school, after taking a printmaking class at Pasadena City College, both my parents encouraged me to make some small, cheap, salable silk screen prints and sell them at gift shops as a summer job, which I did for three summers. I made a good return, probably better than scooping ice cream.

Arcadia Gardens, 1960s

During my high school years, I became fascinated with Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers. I was given an unused corner of the back yard where I was allowed to create my own low-tech version of this vernacular sculpture. I pushed bent, pre-used plumbing pipes into the ground and added plaster ceramic molds to create a kind of re-purposed forest. A discarded bathtub became a small water lily pond, my own modest homage to Monet in an arid environment. I planted cannas and castor bean plants for height, and watermelon vines for the similarity of their leaves to Matisse’s beloved philodendron forms. No one told me to make it look more conventional, and in fact I think my parents liked it as much as I did.

Every year there was a county-wide art exhibition at Barnsdall Park. Anyone could submit their work jury free. I do not remember whether I initiated wanting to show work, or whether my mother suggested it. However, at an early age, probably 11 or 12, I remember her encouragement by loaning me an old frame, and I made a tissue paper collage of red poppies. She drove it into town, along with her own submission. I had the proud experience of seeing my piece hanging along with hundreds of other artists’ works, and it even was sold! Dorothy and her friends were all members of many organizations including Laguna Beach Art Association. With her approval, I applied for membership and was accepted while still in high school. Even while all this art activity was going on, I was still expected to become a MD/PhD.

In 1967, when I went to college (UCSD), I quickly encountered an art department that was way ahead of its time, full of up-to-date ideas and a lot of enthusiasm, taught by knowledgeable working artists. After two years of bio-chem, organic chem and calculus (and no terraria nor aquaria whatsoever), I switched to being an art major. This was difficult for my Dad who was worried that I would never earn an income. But Dorothy was surprisingly supportive. She told me, “If this doesn’t work out, you will have time to try something else.” I think she felt that I was going for a goal that, had she been born 40 years later, she might have reached for herself.

Dorothy’s numerous handmade hats for every occasion influenced Robert Kushner’s “New York Hat Line” Exhibition, 1979. Center image: “Gray Plume,” 1974 (c) Perter Johansky; Right image: “Persian Salt Bag,” 1974, from The New York Hat Line, published by Bozeaux of London Press, New York, 1979. photo © Katherine Landman

At University, everything was taught conceptually. No painting classes, one drawing class, one color theory class, photography, computer programming with lots of art history and art criticism. I was thrilled with the new intellectual horizons presented to me and rejected the unquestioned acceptance of Abstract Expressionism aesthetics that Dorothy and The Group espoused. Conceptual Art was the rage. It culminated for me in a series of costume-sculptures of my own design and construction to be presented ephemerally in the context of what is now known as Performance Art. Over the years, my parents were extremely supportive of my performance art career. I think they found it both a little shocking and also entertaining. They both loved to go to garage and rummage sales, and would frequently send me boxes stuffed with old party dresses, hats, drapes, anything that they thought I could put to good use. For my first show of edible costumes (“Robert Kushner and Friends Eat their Clothes,” 1972) my mother and I spent many afternoons crocheting the skimpy foundations for these costumes.

After graduation, and a year or two in the real world of art making, I realized that I did not know how to draw let alone paint. I began to look more closely at my mother’s work as well as her work ethics and how they had seeped into me almost by osmosis. Painting and particularly drawing, which had been eschewed at university, became active goals again. Color and compositions, two of Dorothy’s strengths, asserted themselves in my work. When she would visit New York, after the trip from the airport, quite often she would put down her bags, say hello to my kids, and then come into the studio to see “what was new”. Of course, precise and sometimes harsh critique was what she had to offer. The Group had disbanded by then, and I think she missed the digging in and the figuring out. Even though it sometimes stung, I was a grateful recipient of her opinions and observations.

“Dorothy Browdy Kushner and Robert Kushner: Reconfigured Flora,” a co-exhibition at Susan Teller Gallery, New York, 2011.

The influences also went the other way, too. In the mid 1970s I was looking at a wide variety of decorative source material, mostly found in textiles, carpets and pattern books. I began drawing from nature for the first time, incorporating botanical forms into patterns. Usually I visited California twice a year for a few weeks at a time, and often I would bring my materials and draw in the back yard. At about the same time, Dorothy started drawing and abstracting flower forms in her own way with her own voice. And why not? We both loved plants, particularly the strong, bold, Mediterranean flora that thrive in Southern California. At another point, I took a workshop about making sculpture with scrap lucite discarded by plastic sign companies. At that time, if you went to these companies and said that you were a student, they would give you tons of scrap plastic. The strong, pure colors, particularly the reds and greens intrigued Dorothy. Working with Joe’s help to cut out and polish her own biomorphic shapes and then create bases for them, she created a body of abstract sculptures, very much three dimensional versions of her high key, late 1960s paintings.

Throughout her adult life, Dorothy painted every day. Whether or not there was acceptance or indifference, she worked, and reworked each piece until it was as fully satisfying to her as she could make it. Nothing was left half-baked. She worked for the satisfaction of working and the quiet joy of new discoveries and resolution.

What better role model could there be for my navigation of the perilous and uncharted waters of the art world? At a certain point in a young artist’s life, if and when attention starts to come, it can become a heady and dangerous experience. Many artists cave in when this happens. Some are paralyzed into repeating their initial success. Others lurch around looking for new ways to recapture their first shock appeal. In my case, I had two important tools. One was meditation and its insistence that one must avoid egotistical attachment to our actions. But the other was my mother’s example. Over many years, I have felt the emphasis shift from a hunger for acceptance to the more sustaining satisfactions of an internal sense of accomplishment.

Toward the end of her life, Dorothy was living in an Alzheimer’s nursing home. I took her to a Chinese restaurant and, to pass time, we played a round of the color-mixing game. I asked her how she would mix a color of the small plate of orangish duck sauce that was put out on the table. There was a very long pause. I had thought that she had forgotten or not understood my question, and then finally she said, speaking slowly but clearly: “I would start out with Cadmium red deep and white, then start adding yellow.” While words were simply too difficult for her by that time, she could still analyze the chromatic components.

She remained, as she has always been, a true artist to the core, and a tremendous gift to me.

Robert Kushner, New York 2015